SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — They were teammates for 10 years with the Seattle Mariners.

They have been in the Baseball Hall of Fame together for nearly eight years.

The duo combined for 23 All-Star appearances. Johnson won five Cy Young awards. Griffey was an MVP.

Now, here they are, 35 years after first meeting, spending more time talking about their passion of photography than they ever did about baseball:

While Griffey is engrossed in sports photography, and is a credentialed photographer at some the biggest sporting events in the world from the Super Bowl to baseball’s recent Korea Series, Johnson has been captivated by the beauty of Africa, where he has taken breathtaking pictures from the animal kingdom to natives in villages.

MLB SALARIES: Baseball’s top 25 highest-paid players in 2024

“Randy has been interested in photography for a long time,’ Griffey says, “and when I saw some of his photos from his Africa trips, you can see how talented he is. He’s gone through some villages and taken some unbelievable photos of the villages, people in villages, animals, he’s captured some really positive and nice images.

“And he’s got to be the tallest photographer in the world, too.’

Indeed, you don’t see 6-foot-10 dudes walking around taking pictures in Africa, every day. Then again, you don’t see photographers on football sidelines who have 630 home runs on their resume, either.

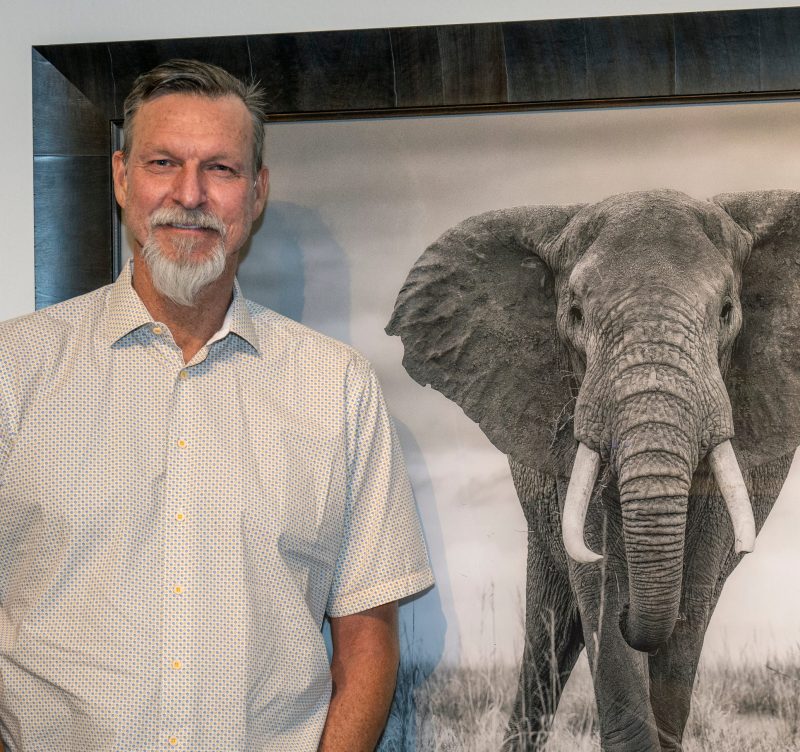

The two of them, who have discussed venturing on an African trip together one day, talked to USA TODAY Sports, about their love for photography, with Johnson providing an hour-long tour of his photo exhibit at the Scottsdale Center for the Performing Arts.

“This is just a passion of mine,’ Johnson says, walking around the studio. “I’m not a professional. I don’t shoot for National Geographic. My satisfaction is that I get to share these pictures with people that may never go to Africa.

“It’s pretty impactful, the stuff you see over there, some of it can be life-changing.’

Just like he did throughout his 22-year playing career, Johnson again is striving for perfection.

“Obviously, when you come to a baseball game and you watch me pitch,’ Johnson says, “I can’t fool you. If you know anything about baseball, you will know if I pitched a good game or a bad game. But you’re here to look at my art, and that’s completely subjective.

“If you can just touch one person, impact one person, I think these photos do more that. Kids can come in here and have the same dream like mine, to play professional baseball. If that doesn’t work out, well, pick up a camera, or maybe you can do something in the art world. You’re not a geek because you take pictures.

“I know. I do it. I love it.’

Griffey reels off a few former athletes he knows that are into photography, particularly sports, with everyone from former Pro Bowl receiver Larry Fitzgerald to former All-Star and batting champion Michael Cuddyer.

“There’s probably a 100 of us, low-key photographers,’ Griffey says. “It’s so nice to see. Photographs are so much different than sports. You’re not competing against anyone, you want to help the next person.

“There are so many people that have reached out and helped me.’

Johnson, who studied photojournalism at University of Southern California, began taking pictures at rock concerts. He was a huge music fan, with access to performers such as Elton John and Billy Joel and bands like Rush and Metallica. Griffey laughs remembering walking into Johnson’s Seattle home for the first time and seeing a studio and professional drum set.

Johnson’s photography has evolved into a handful fo trips to Africa. He proudly shows pictures he has taken of 600-pound silverback gorillas in Rwanda, the migration of wildebeest in Tanzania, elephants, leopards, cheetahs, alligators, natives of Ethiopian villages, and a young Kenyan boy who’s discriminated against in his country for having dark skin and bright blue eyes.

“To not have any friends and be ostracized from society because of how you look,’ Johnson said, slowly shaking his head. “Well, that still happens in our society.’

There are stories behind each of the 30 photos with Johnson saying the great migration is the original reason he wanted to visit Africa and he became enthralled after all of his research, resulting in a handful of trips.

“Africa offers a lot more than just animals,’’ Johnson said. “It was probably the third or fourth time that I went to Africa and had my Ethiopia experience. Just the opportunity of seeing this every day, living in a tent outside of their village, and interacting with a lot of these people, was just fascinating.’

In many ways, Johnson said, he judged each experience as if he were still a pitcher, only with no box score to reveal the quality of his outings.

“I wanted to take it to the next level,’ Johnson said, pointing to different photographs. “It’s like progressing from the minor leagues to the major leagues. Some of my earliest photos were minor league-ish. These were like giving up three runs but now pitching a two-hit, 12-punchout, shutout.

“There’s a lot of parallels between pitching and photography. When I put my camera up to my face, the only thing I see is the subject that I’m taking a picture of. When I put my glove up to my face to get the sign, all I ever saw was my catcher and the batter. I blacked out all of the noise. So it’s the same focus.’

When asked to identify his favorite photograph at his photo exhibit, Johnson shrugged, and said, “There’s no perfect game in here.’’

At least, he says, not yet.

“I know personally having pitched a perfect game, and it was towards the end of my career [age 40], it was just magically one of those things that happens,’ he says. “So, I know I have the ability to get that picture.’

Johnson, who still is recovering from knee surgery, last visited Africa in August for three weeks. Griffey, who had a lengthy conversation with Johnson for advice, visited Kenya in December.

One day, whenever their schedules line up, they hope to be together taking pictures in Africa. Johnson loves the fact that despite his size, nobody recognizes him. The same with Griffey, who can walk around villages without the attention that comes with being one of baseball’s all-time greats.

“Some people didn’t even pay attention to me,’’ Johnson says, “which is refreshing. I love that. I could do what I wanted to do, to the best of my ability, because I wasn’t looking over my shoulder.’

It’s much more different than in this country where folks recognize him, stop him on the streets or in restaurants, and ask for autographs or selfies.

The baseball world, Johnson says, is behind him now.

He loved playing the game, but doesn’t want to sit around and take pictures of it.

He wants to tell new stories through his camera lens, not share ones of his baseball past.

“The connection I had with sports is that I played it,’ Johnson said. “For me to sit in a photo well and take pictures of someone that wasn’t even born when I was playing … I’d be missing out on other opportunities.

“This is the stuff I enjoy, or just traveling in general. At this time of my life, I’m 60 years old, this is what I got, this is what I live for.’

While Johnson has no real interest in sports photography, when he looks back at his career, he thinks about how cool it would have been if he brought his camera on the road. He played with some of the greatest players in the game with Griffey, Alex Rodriguez, Edgar Martinez and Jay Buhner on those star-studded Mariners teams.

“Can you imagine the pictures that I would have on the Seattle Mariners,’ Johnson says, “of like [Ken Griffey] Sr. hitting a home run and then Jr. hitting a home run and their excitement in the dugout. Or taking pictures on the airplane, or guys having fun celebrating a win.

“I think what would have been cool if I had taken pictures of the ballparks I played in, Tiger Stadium and Old Comiskey Park, Cleveland, and old Yankee Stadium.’

He may not have old baseball shots, but he proudly possesses a photo he took at USC. He was walking around campus in 1983 and saw a beat-up Mini Cooper in a dumpster, courtesy of a fraternity row prank.

That same picture is now enlarged and hanging in his home.

Griffey’s favorite pictures are in the family album, with son Trey catching his first touchdown pass in college at the University of Arizona, son Tevin returning his first interception for a touchdown at Florida A&M and Taryn making her first basket at Arizona.

“I started picking it up watching my kids play,’ Griffey said, “because nobody bothers the photographer, really. But I enjoy my time with other photographers. There’s not one photographer who didn’t want me to get better. Having that network of guys at your disposal, there’s a bunch of people that helped myself and Randy.

“That’s the one thing you learn, somebody’s always going to be better, or have an idea that you may not may have thought of. I want to learn it all.’

Says Johnson: “I’m so excited to see that he’s gotten into that. I think he’ll get to the point where he really enjoys it. I know this has had a great effect on me.

“Really, there’s so many parallels to baseball, a lot of studying, and a lot of practice. I really want to be good at it. I don’t want to put up mediocre stuff. I strive to be better until I can’t take pictures anymore.

“I have really put my heart and soul in this, and I just hope people appreciate it.’

Who knows, Johnson and Griffey and all of the other former professional athletes turned amateur photographers, can one day turn their art into a lasting legacy.

“It would be pretty cool,’ Griffey says, “to get everyone together and do something for charity with our pictures. That’d be pretty special.’

Teammates once again, only this time, with a camera lens.

Follow Nightengale on X: @Bnightengale